Phylogeny is the conceptual and practical framework for studying biodiversity from an evolutionary perspective. My research program unifies hypothesis testing with data-driven approaches in phylogenetics to uncover the factors that generate evolutionary patterns—a concept that has been called “Phylogenetic Natural History” (Uyeda et al 2018). In my work, I have applied the concept of “Phylogenetic Natural History” by merging domains of natural history, data science, computational biology, paleontology, and genomics.

Deep-time natural history through the lens of molecular evolution

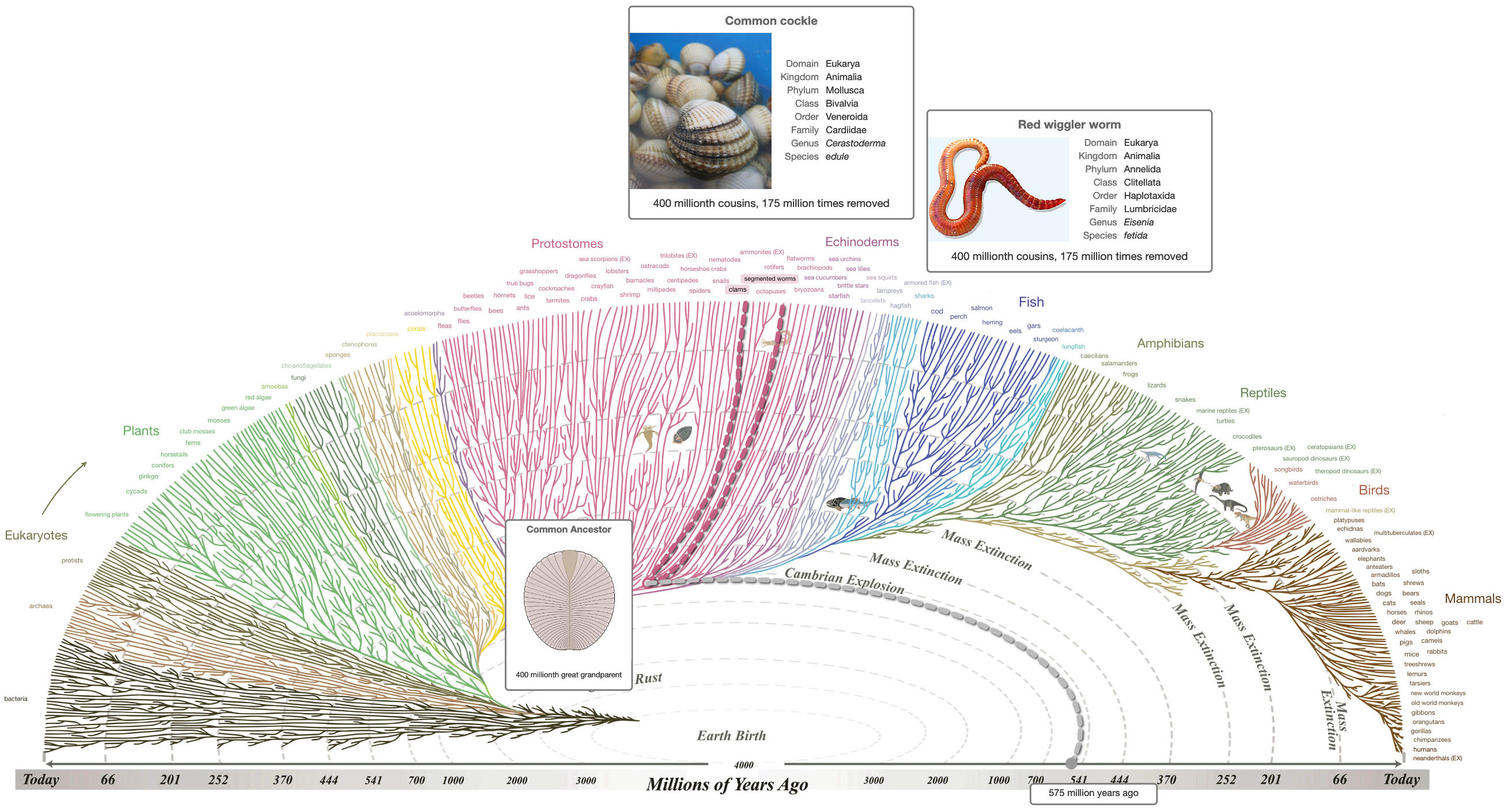

Resolving the evolutionary history of groups of organisms that are suspected to have rapidly diversified is a fundamental challenge in systematic biology – and one which tests the limits of what can be known. My current research interests in this topic are motivated by the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs and the subsequent diversification of vertebrate clades towards the end of the Mesozoic 66 million years ago (the K—Pg boundary).

Phylogeny Inference

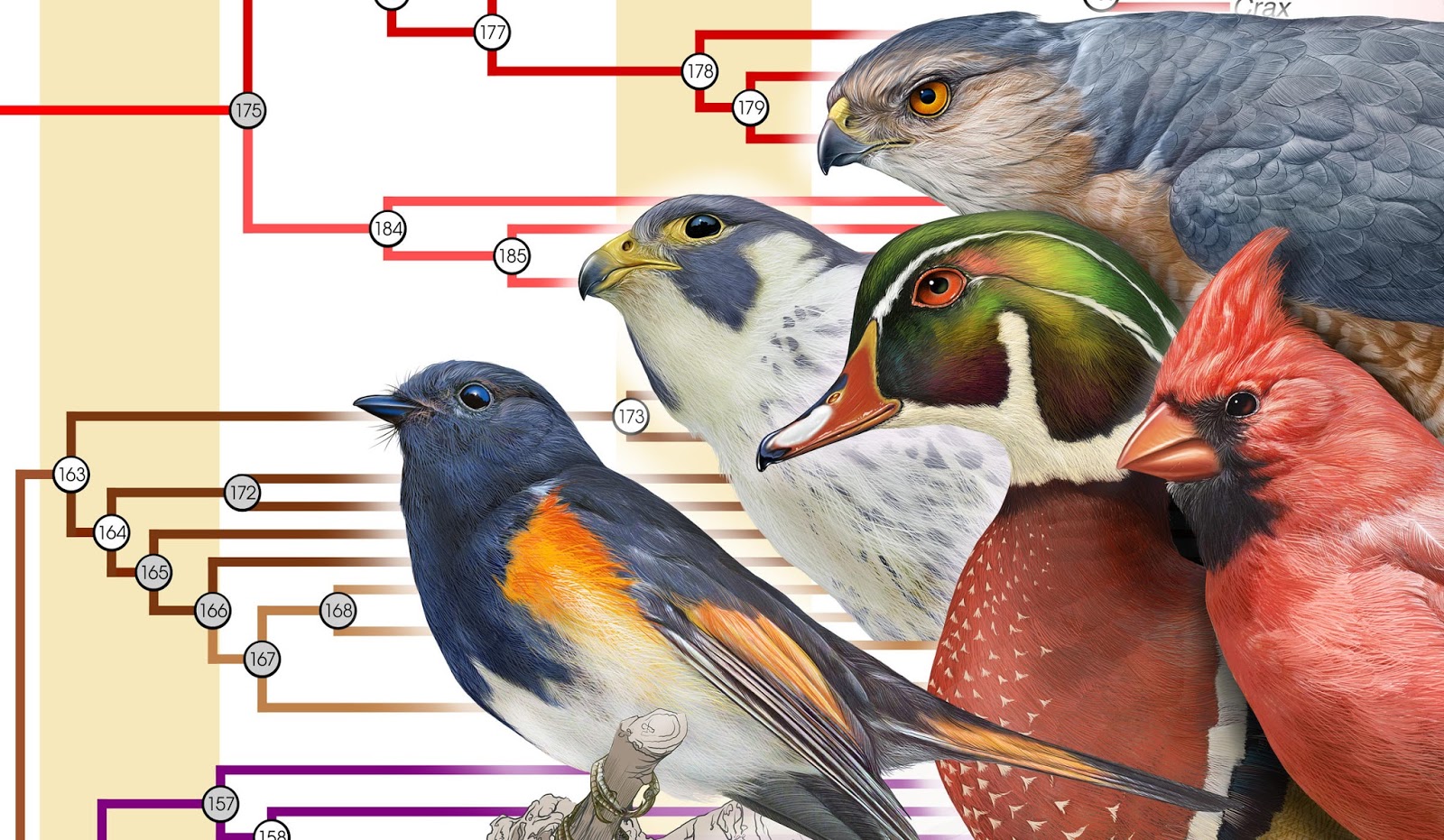

The inference of the structure of the tree of life is a primary goal of systematic biology. Here, I highlight one example of phylogenetic inference in my research that 1) investigated the relationships among modern bird families and 2) estimated a new timescale of avian diversification (Prum, Berv, et al. 2015, Nature). In this project, we leveraged advances in target-capture DNA sequencing to estimate that the diversification of modern birds comprises nine super-ordinal groups which evolved in close association with the K—Pg boundary. We presented strong support for novel relationships and the first “next-generation” phylogenomic evidence for hundreds of key relationships across the avian tree of life. In addition, we advanced several statistical approaches for phylogenetic experimental design. These approaches, which include metrics of “phylogenetic informativeness,” empower researchers to design phylogenetic inference studies to have maximum statistical power to address specific questions. Download PaperDownload Poster

Divergence time estimation

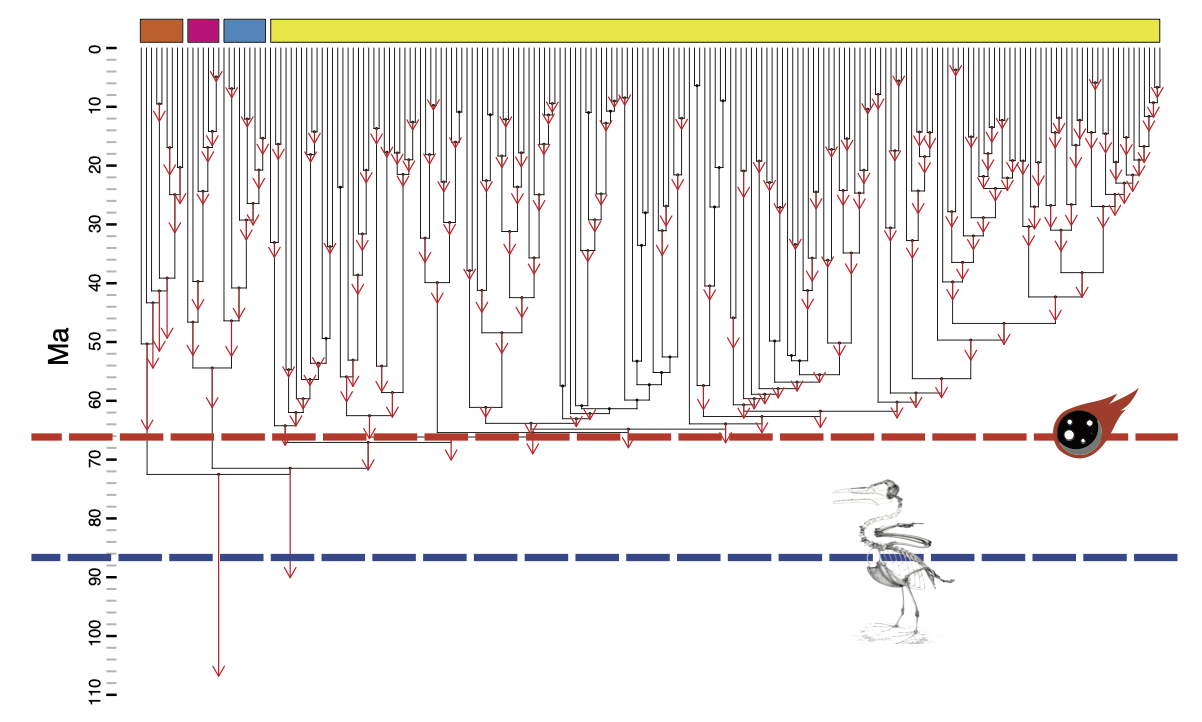

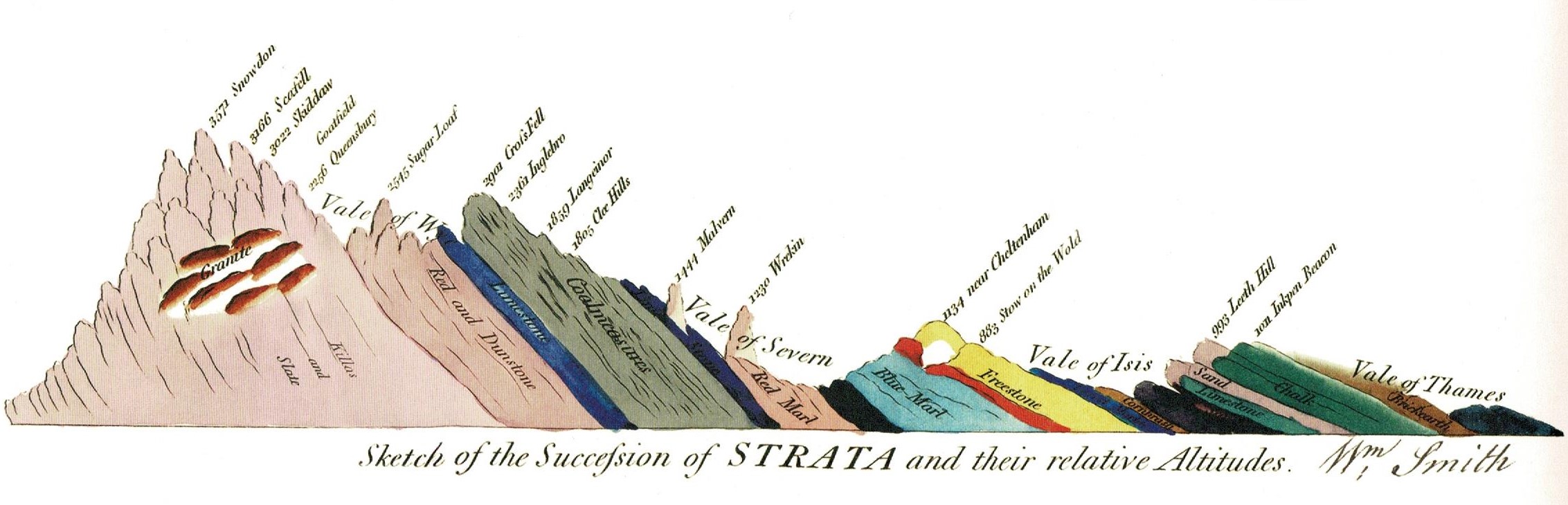

A longstanding issue in systematic biology is that there is often conflict in signals of when groups of organisms arose. For instance, inferences based on the fossil record and inferences made from molecular sequences are often incompatible. Such discrepancies between the fossil record and the signal in molecular data make it difficult to reliably assess the impact of events in Earth’s history on the diversification of life’s major groups. Taking birds as an example, the fossil record implies that major sub-groups originated close to the K—Pg boundary (~66Ma). In contrast, molecular-clock estimates often indicate much older ages (100-150+ Ma).

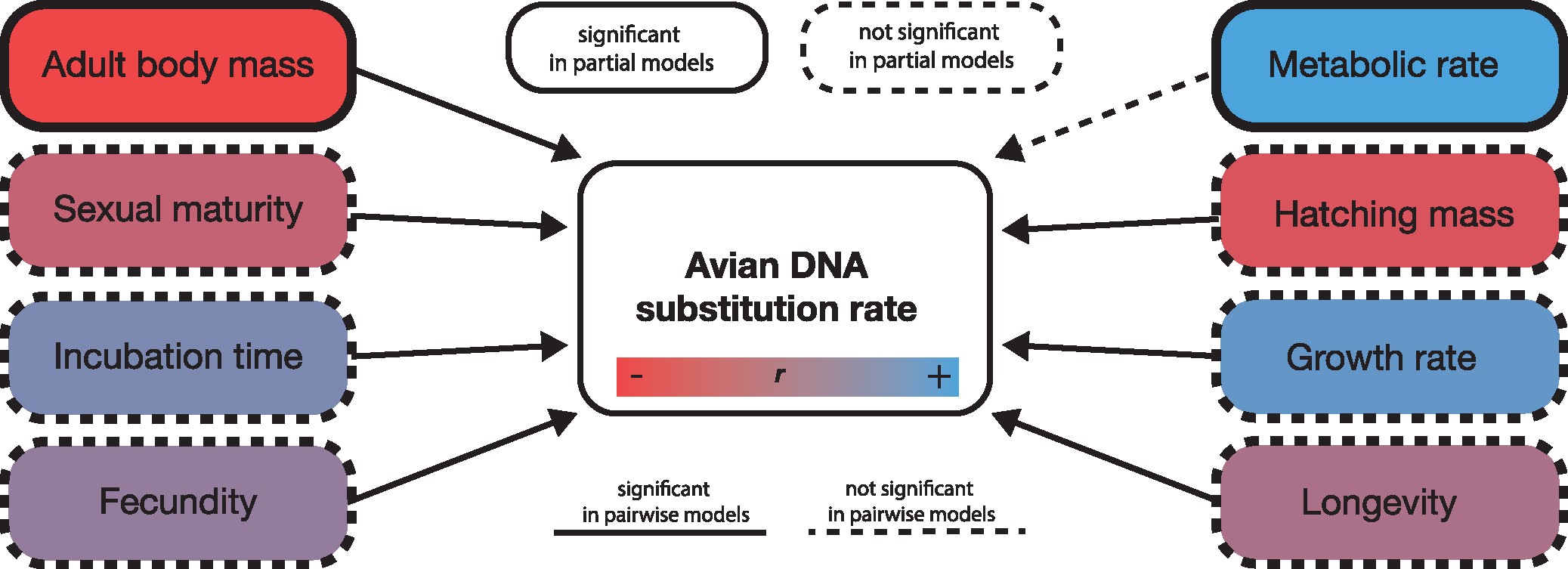

In Berv and Field 2018, Systematic Biology, we investigated the hypothesis that a K—Pg-induced acceleration in the rate of avian genome evolution may explain part of this discrepancy. Our hypothesis is derived from fossil evidence that mass extinctions can select against large-bodied organisms through several mechanisms known collectively as the “Lilliput effect.” Because smaller-bodied birds also tend to have faster-evolving genomes, the presence of an “Avian” Lilliput effect across the K—Pg boundary may induce systematic bias in addressing fundamental questions about the origin of modern birds. We suggest that integrated evolutionary responses to mass extinctions (e.g., from the genome to the species) may apply to other groups of organisms—and may artificially inflate estimates of divergence times implied by molecular sequences. Download Paper2019 Defense SeminarPublisher’s Award

The Tempo and Mode of molecular evolution

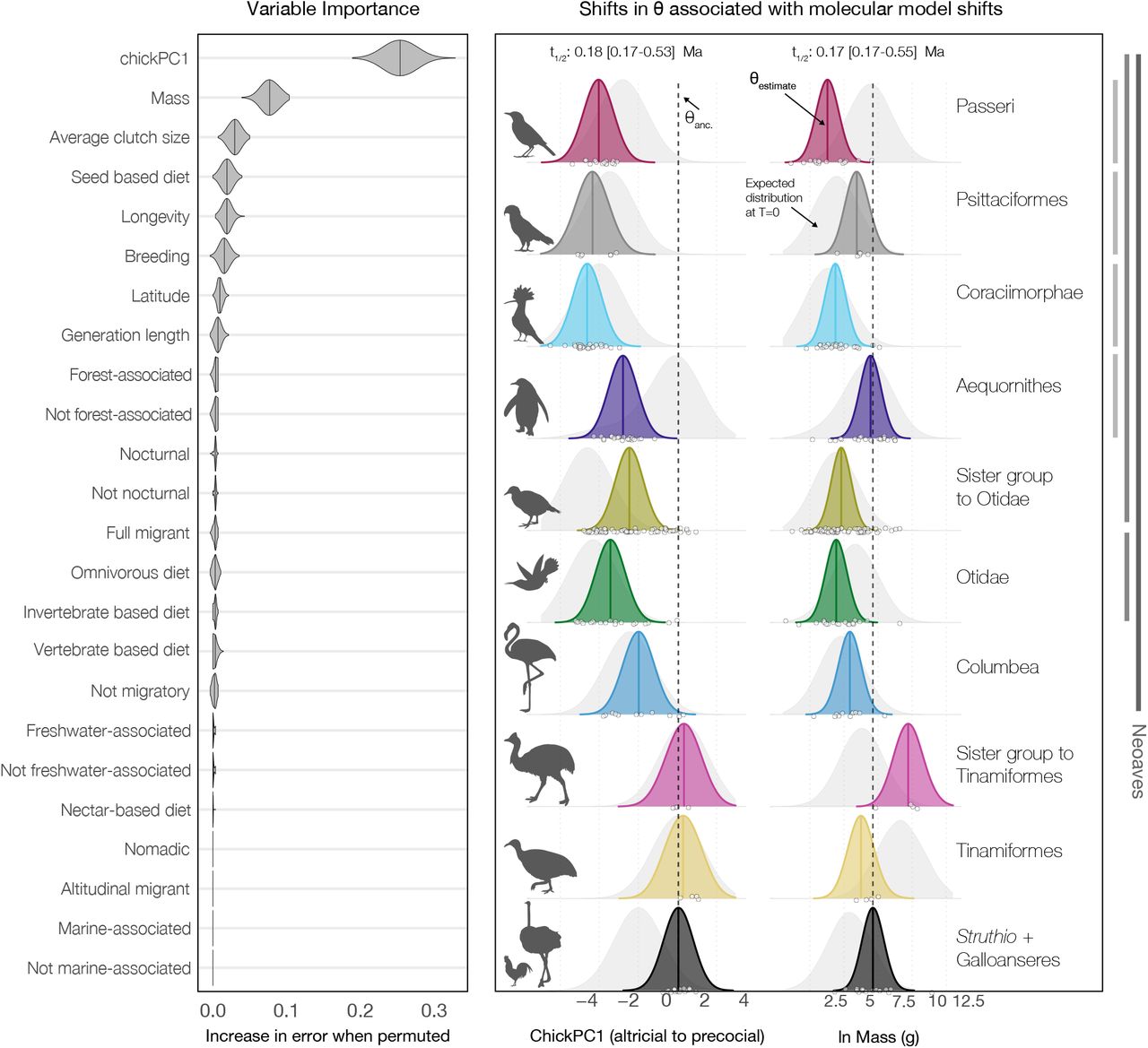

As a Life Sciences Fellow at the University of Michigan (2019-2023), I have explored the idea that variation in both the “tempo” or speed, and “mode” or processes of evolutionary change can confound the interpretation of phylogenetic data. In research now available on bioRxiv as a preprint, I investigated molecular model heterogeneity across crown bird phylogeny using a technique enabling inferred sequence substitution models to transition across the history of a clade. In essence, this allows us to infer transitions in the evolutionary process that generated the sequence data we are able to observe today. Using these tools, I identified distinct patterns across exons, introns, untranslated regions, and mitochondrial genomes that reflect shifts in key processes of molecular evolution. Multiple model shifts map to lineages originating shortly after the end-Cretaceous extinction, demonstrating a burst genome evolution early in the evolutionary history of birds. In addition to increasing our knowledge of macroevolutionary patterns, our study provides strong evidence that deep-time shifts in processes of genome evolution were associated with changes in avian life history, physiology, and development. Download preprintSeminar recording

Patterns ofmolecular evolution

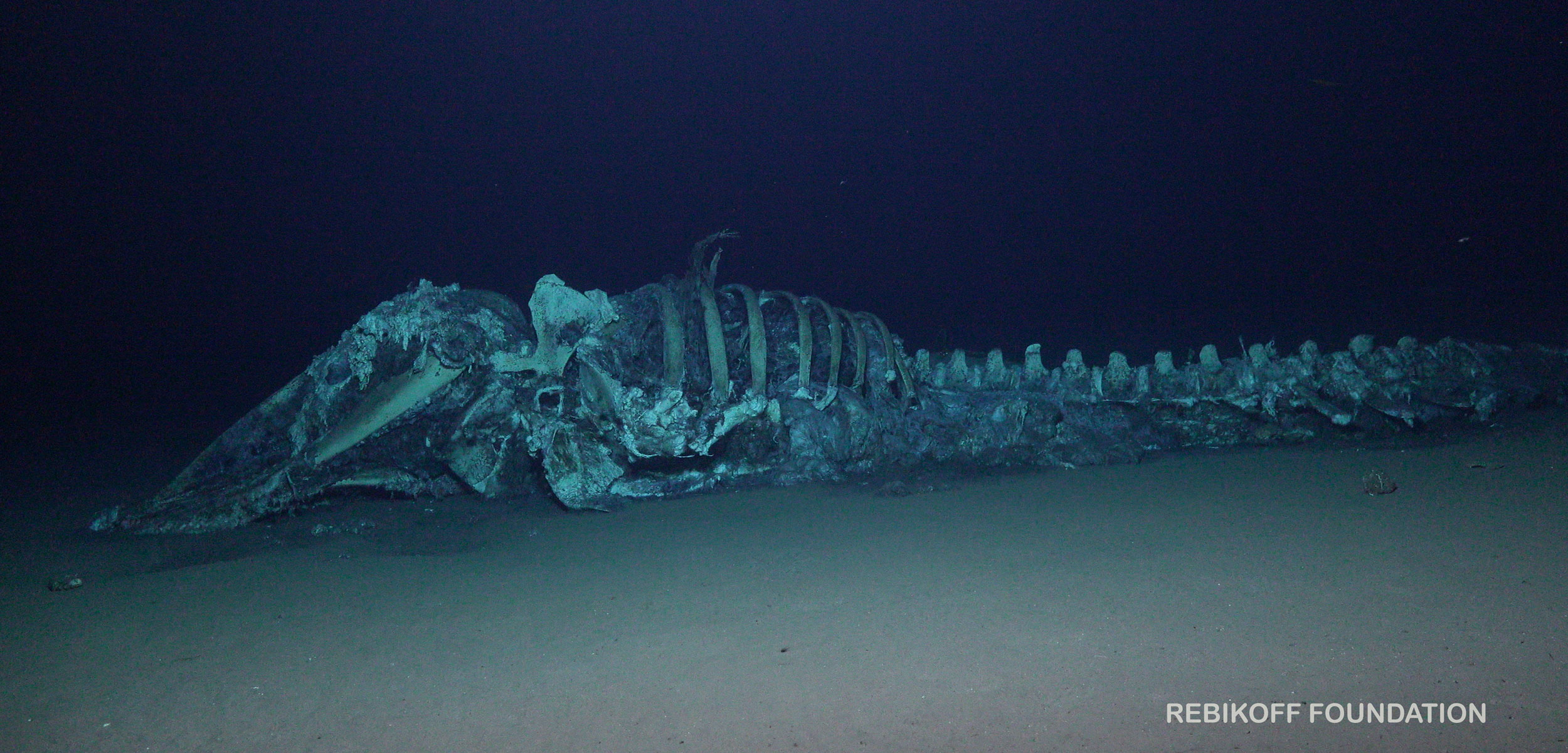

Using a natural experiment in the energy-starved deep sea, where mussels and tubeworms have diversified across chemosynthetic environments, Cornell PhD student Amelia Weiss and I investigated a novel resource longevity hypothesis that predicts an inverse relationship between the longevity of limiting resources and consumers’ rates of genome evolution.

In the deep sea, organic falls (e.g., whale falls), hydrothermal vents, and cold seeps create ephemeral patches of productivity that persist over different lengths of time, ranging from decades to millennia. These longevities induce a hard maximum on a community’s life cycle, and thus, are predicted to select for consumers with life-histories adapted to ephemeral resources.

As variation along the life-history spectrum often corresponds with variation in the rate of genome evolution, we predicted a signature of habitat longevities might be recorded in the genomes of consumer specialists. Our study documents the first example (to our knowledge) of a widespread relationship between habitat longevity and rates of mitochondrial evolution. A preprint describing these results will be available soon.